Australia: a tangled web of class actions

Australia has become one of the most plaintiff-friendly countries in the world for securities class actions. Now big business is calling for change.

In 2017, the 500th class action was filed in Australian courts, 25 years since the first. An average of 20 class actions each year would hardly seem to make the country a litigation hotbed, but the sharp increase in recent years in the number of class actions filed against public companies and the size of settlements reached has made Australia a land of opportunity for plaintiff lawyers.

“Australia is becoming as litigious as the US for listed companies,” says Gary Lill, D&O Line Underwriter with Hiscox. “Many more class actions are filed in the US, but relative to the number of public companies, the percentage being sued is comparable. Last year, 16 companies in the ASX300 [the index of the top Australian listed companies] had securities class actions filed against them. That equates to 5% of the ASX300, akin to the rate in the US.”

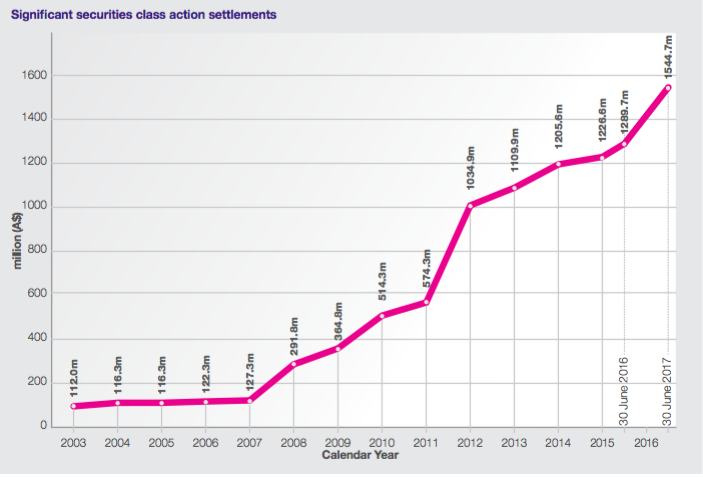

Source: King & Wood Mallesons

To tell or not to tell

Several aspects of Australian law make it one of the most plaintiff-friendly countries in the world. Public companies have a duty of “continuous disclosure” to tell the market as soon as possible of any information that might affect their share price. “What a company should disclose and how quickly is often a grey area and a challenge for public companies,” says Lill. But bad news that knocks a company’s share price will often prompt plaintiff law firms to launch class actions alleging the company withheld information, causing shareholders to lose money.

Public companies have a duty of “continuous disclosure”. But what information a company should disclose and how quickly is often a grey area.

Companies can also be held liable for “deceptive and misleading conduct” – a sort of false advertising law that also covers corporate conduct. “It’s a unique feature of Australian law that is extremely broad,” says Tim Searle, a Perth-based Partner at Clyde & Co. It not only covers what a company says but also what it doesn’t – silence can also be legally interpreted as being disingenuous.

So Australian companies may find themselves in a catch-22: they need to decide straight away whether to inform the market, but their statements might be seen as misleading investors. Either way they risk being sued.

Easy to sue

The legal hurdles for bringing class actions are much lower in Australia than in the US or UK. Even the fact that Australia has a “loser pays” rule, so the unsuccessful party in a court action pays both sides’ legal costs, hasn’t put a dampener on the number of class actions for two reasons.

Firstly, specialist firms are allowed to bankroll litigants’ costs in Australia. The fertile environment for class actions has prompted a sharp rise in the number of litigation funders in recent years and there are currently around 22 in existence. Only a few years ago it was a handful. “It’s a thriving business” says Lill.

The fertile environment for class actions has prompted a sharp rise in the number of litigation funders in recent years and there are currently around 22 in existence.

Secondly, most securities class actions are settled long before they reach court. Only four have ever reached trial and only two have gone as far as a full trial. None have reached a final judgment.

Plaintiff lawyers and litigation funding firms will often drum up support for a potential class action in the media before actually filing the formal paperwork with the courts, unlike in the US. They will look to ‘build’ a class before filing the lawsuit in the same way a stockbroker puts together a book of potential investors before a share issue. The publicity campaign can knock a company’s shares badly enough that they’ll choose to settle a class action even before it is filed with the court.

Plaintiff lawyers and litigation funding firms will often drum up support for a potential class action in the media before actually filing the formal paperwork with the courts, unlike in the US.

Royal brouhaha

A royal commission looking into accusations of wrongdoing in the financial services industry is also generating a string of lawsuits.

It has heard allegations of bribery, misselling, lying to regulators and even charging dead clients for financial advice. The revelations have already reportedly led to 20 class actions being filed – five against one company alone – and more are likely as the commission continues to hear more evidence throughout this year. “The royal commission is proving to be a real hotspot for class actions,” says Searle.

The litigation will heap more misery on the country’s beleaguered D&O insurance market. The total value of securities class action settlements between 2003 and the end of June 2017 was just over A$1.5 billion (US$1.1 billion), according to research by law firm King & Wood Mallesons. “There is an estimated A$1.2 billion to A$1.8 billion in further settlements in the pipeline, excluding those class actions prompted by the royal commission,” says Lill. Such big claims are a heavy burden for a market worth around A$250 million in premiums each year.

A royal commission looking into accusations of wrongdoing in the financial services industry is also generating a string of lawsuits.

D&O premiums have soared as a result, with some companies being charged 400% more for cover this year. Increases of between 40% and 70% are regarded as being good results, even though many companies will be forced to retain more risk. The Australian financial and professional lines market, which includes D&O, is the hardest market in the global insurance industry, according to a recent report by Marsh.

Some insurers are cutting their capacity while others are exiting altogether. A number are reportedly looking to impose exclusions to prevent them having to cover class actions resulting from the royal commission. Several are warning that so-called Side C cover, which compensates the company for class actions alleging corporate wrongdoing, rather than against its executives, is unsustainable. Lill disagrees. “It’s insurable, providing you can price in the risks and set the right terms.” What is urgently needed, he adds, is “a real change in all parties' mindsets” in a market where historically cover was too broad, with inadequate premium and retentions.

Change on the cards?

Businesses have been pressing for changes to curb the rising number of class actions which has resulted in their skyrocketing insurance costs. In June, it looked like their prayers had been answered.

The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) issued a discussion paper addressing many companies’ main complaints, including proposals to review the rules on continuous disclosure and deceptive and misleading conduct, and the regulation of litigation funders.

“It would be surprising if at least some of these recommendations weren’t accepted,” says Searle. Australia has acted in the past to address insurance capacity crunches, he explains, bringing in sweeping changes following the collapse of HIH Insurance to encourage other insurers to provide professional indemnity cover.

But, Searle says: “I’d be astonished if either the continuous disclosure or deceptive and misleading conduct rules were changed. I don’t think that relaxing corporate disclosure obligations would be politically palatable right now.”

Businesses have been pressing for changes to curb the rising number of class actions which has resulted in their skyrocketing insurance costs.

Regulating litigation funders for the first time is more likely, Searle suggests. A licensing scheme, including a code of conduct and an annual audit, could create a barrier to entry for new players and therefore put a brake on the industry’s explosive growth.

Putting an end to competing class actions alleging the same wrongdoings is another recommendation that could be adopted, Searle says. Australian courts have often allowed several class actions to run concurrently, adding to the time and expense incurred by both plaintiffs and defendants.

While those changes might reduce the number of large class actions, another proposal could prompt more lawsuits.

Enabling law firms to charge contingency fees for the first time would, the ALRC argues, create more competition between class action lawyers and litigation funders. That should result in lower fees for plaintiffs, but it could also lead to more medium-sized class actions being launched, the ALRC states. Meanwhile, new rules make it easier for litigation funders to recover their money once cases are settled, even from those class members that didn’t agree to use a funder’s money to bankroll the costs.

Wait and see

It remains to be seen which reforms the ALRC makes in its final report, due at the end of this year, and whether lawmakers decide to adopt them in a country where class actions are seen as an important way of holding big business to account. But there’s an increasing recognition that the current class action system doesn’t always guarantee justice for all. In the meantime, Australian companies will anxiously hope that further startling revelations of wrongdoing from the royal commission won’t undermine their calls for D&O cover to be made more available and affordable.