Cubesats have come of age

It’s 20 years since the first “cubesat”, a small satellite the size of a shoebox, went into space. Since then, these little boxes of tricks, made using the same off-the-shelf electronics used in smartphones and digital cameras, have revolutionised the satellite industry and transformed our daily lives.

Cubesats were initially intended as a student project at Stanford University whose design was inspired by the 90s miniature toy craze Beanie Babies. They can be built and launched in months, which is a fraction of the time it takes to build a conventional satellite, and at a fraction of the cost too. This has meant that for the first time, small countries, start-up companies and universities can afford a satellite.

“Today, we depend on cubesats for so many things which we now take for granted,” says Pascal Lecointe, Space Line Underwriter at Hiscox London Market. “We rely on them to track planes and ships, provide high-definition imaging, detect earthquakes sooner, track climate change, help planners to design cities and farmers to decide which crops to grow.”

“Today, we depend on cubesats for so many things which we now take for granted,” says Pascal Lecointe, Space Line Underwriter at Hiscox London Market.

Their number has mushroomed as they’ve proven their worth. Between 2003 and 2018, around 750 had been launched into space. Since then, the number has more than tripled, to 2,323 as of 1 January 2024, according to the Nanosats database, and the small satellite industry is booming, and could be worth $7 billion by 2028.

Their low cost and short lifespans meaning they may last only a year or two, has meant that many operators choose not to insure them. “That wasn’t a problem for space start-ups until a year or two ago, because if one satellite failed then their investors would write a new cheque for another one,” says Pascal Lecointe, Space Line Underwriter at Hiscox London Market. “But now money is much tighter.”

Has the bubble in space investment burst?

SpaceX and Blue Origin kickstarted a new era of space exploration, and investors poured money into the fast-expanding space industry, particularly the satellite-launch business. But now investors are worrying if they’ll ever make a return.

Space’s share of the US economy shrank between 2012 and 2021, government figures show, largely because of a huge shift away from satellite TV to internet streaming. Other industries are growing faster, making them more attractive investments for venture capital funds.

A recent report on the future of the space economy by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) states: “There are growing concerns about medium and long-term access to private as well as public sources of funding.”

Many in the space industry expect government funding will fall because of budget squeezes resulting from the global economic headwinds. National space agencies are an important source of seed capital to develop new space technologies as well as being big customers, which helps to attract private funding, the OECD states.

Now the investment bubble in space has gone that could make it harder for companies to raise more money. Investment more than halved in 2023, at less than $18 billion down from a high of $47 billion in 2021, according to Space Capital.

So, investors will be less willing to cover the costs of building and launching a new satellite if the first one fails to reach orbit.

Space junk and solar storms

The fact remains that launching satellites into orbit remains a risky business. “Cubesats had a 15% probability of failure before their missions began, higher than conventional space missions according to our analysis of launch data between 2003 and 2018,” says Lecointe.

“The figures have improved in the past five years, but there is still a 10% probability of a satellite not starting its mission. And with the arrival of a new generation of launch vehicles, the chance of success could actually regress in the next few years,” says Lecointe.

“The figures have improved in the past five years, but there is still a 10% probability of a satellite not starting its mission. And with the arrival of a new generation of launch vehicles, the chance of success could actually regress in the next few years,” says Lecointe.

And the risks to a satellite once it’s in orbit are rising. Collisions between satellites and the millions of pieces of space junk will become more common, space experts fear, especially in the cluttered low-Earth orbits in which cubesats operate. There is now likely to be a “destructive collision” between a spacecraft and a piece of space debris every ten years, the European Space Agency forecasts – a much higher risk than ever before.

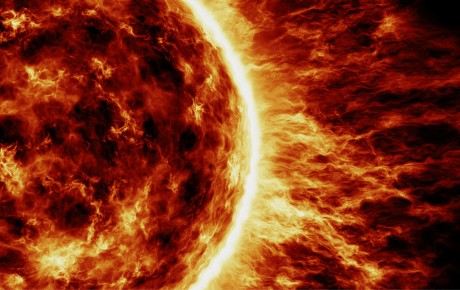

Also, scientists predict there could be powerful solar storms this year that could damage or destroy satellites, when the sun reaches its maximum, increasing the risk that huge explosions of energy could be fired off from it travelling at millions of miles an hour, known as solar flares and coronal mass ejections. In 2017, two huge solar flares sent satellite-based GPS navigation systems haywire for a time.

So, with everyone in the space business tightening their belts, buying insurance could be the safest bet for more cubesat makers and operators.

“There have been great strides forward in cubesats in the past 20 years,” says Lecointe. “They’ve become more reliable, but the risks to them are still large. Insurance is a prudent risk management option, because, if something goes wrong, it offers cubesat owners an alternative source of capital to seeking fresh finance from investors, which is increasingly challenging in today’s tougher climate.”